Rhetoric, Authoritarianism, and the American Political Divide

The collapse of the Soviet Union at the close of the Cold War did not merely mark an ideological victory for capitalism; it presented the American political right with a powerful new rhetorical opportunity. In the absence of a visible, organized communist threat, the conservative movement employed a strategy that conflated all forms of collective economic thought—including democratic socialism—with the totalitarian excesses and failures of state-led communism. This rhetorical framing successfully mobilized conservative opposition by painting the entire left-leaning policy spectrum as a prelude to dictatorship, a dynamic that continues to shape American political polarization today.

The primary mechanism of this political exploitation involved leveraging the visceral, anti-communist fear that defined the Red Scares and the Cold War era. By deliberately blurring the lines between Marxist-Leninist communism and democratic socialism, conservative figures could effectively tar modern progressive reforms—such as universal healthcare, infrastructure spending, or expanded social welfare programs—as “creeping socialism,” indistinguishable from the brutal, one-party states of the 20th century. This strategy, which critics argue is more about casting a negative light on political opposition than reflecting governing philosophy, was particularly effective in the post-Cold War vacuum where the “socialist” label could be repurposed to discredit Democrats and liberals who championed larger government roles.

Crucially, this political rhetoric overlooks fundamental constitutional and political distinctions. Communism, in its historical, implemented form (Marxism-Leninism), demands the revolutionary overthrow of existing political and economic structures, typically establishing a totalitarian, one-party state with collective ownership of all means of production and the abolition of private property. Such a system is inherently incompatible with the US Constitution, which safeguards private property, freedom of association, and the democratic processes of multi-party elections.

In sharp contrast, democratic socialism, while sharing the long-term goal of increasing economic equality, operates entirely within the established constitutional framework. Democratic socialists seek reform through existing democratic means: elections, legislation, and public debate. It generally advocates for policies like a robust welfare state, public ownership of key infrastructure, and stronger labor protections, often within a mixed-market economy, similar to many successful European nations. Democratic socialism explicitly rejects the authoritarianism and revolutionary violence associated with communism, grounding its aims in political pluralism and civil liberties. Legally and practically, a democratic socialist movement is wholly constitutional, defined by its adherence to democratic institutions.

Beyond rhetoric, some political psychologists and sociologists have analyzed the psychological underpinnings of political extremism on both the far-left (historical communism) and the modern political right, frequently citing the work of Theodor Adorno and his colleagues in The Authoritarian Personality (1950). This landmark study sought to identify the psychological syndrome that predisposes individuals to embrace fascism and rigid social structures. The “authoritarian personality” is characterized by traits such as:

- Conventionalism: A rigid adherence to conventional, middle-class values.

- Authoritarian Submission: An uncritical, submissive attitude toward idealized moral authorities of the in-group.

- Authoritarian Aggression: A tendency to condemn, reject, and punish people who violate conventional norms.

- Power and Toughness: A preoccupation with the dominance-submission dynamic.

While Adorno’s initial work focused on the fascist threat, subsequent academic analyses have identified similarities in the structure and function of extreme political movements. Authoritarian regimes, whether of the totalitarian communist or fascist variety, share an insistence on ideological purity, a cult of personality around a powerful leader, and the suppression of dissent. In contemporary American politics, analysts who apply this framework argue that a type of “pseudoconservatism,” characterized by a sense of powerlessness leading to a yearning for a strong, simplified, and destructive form of authority, has taken root.

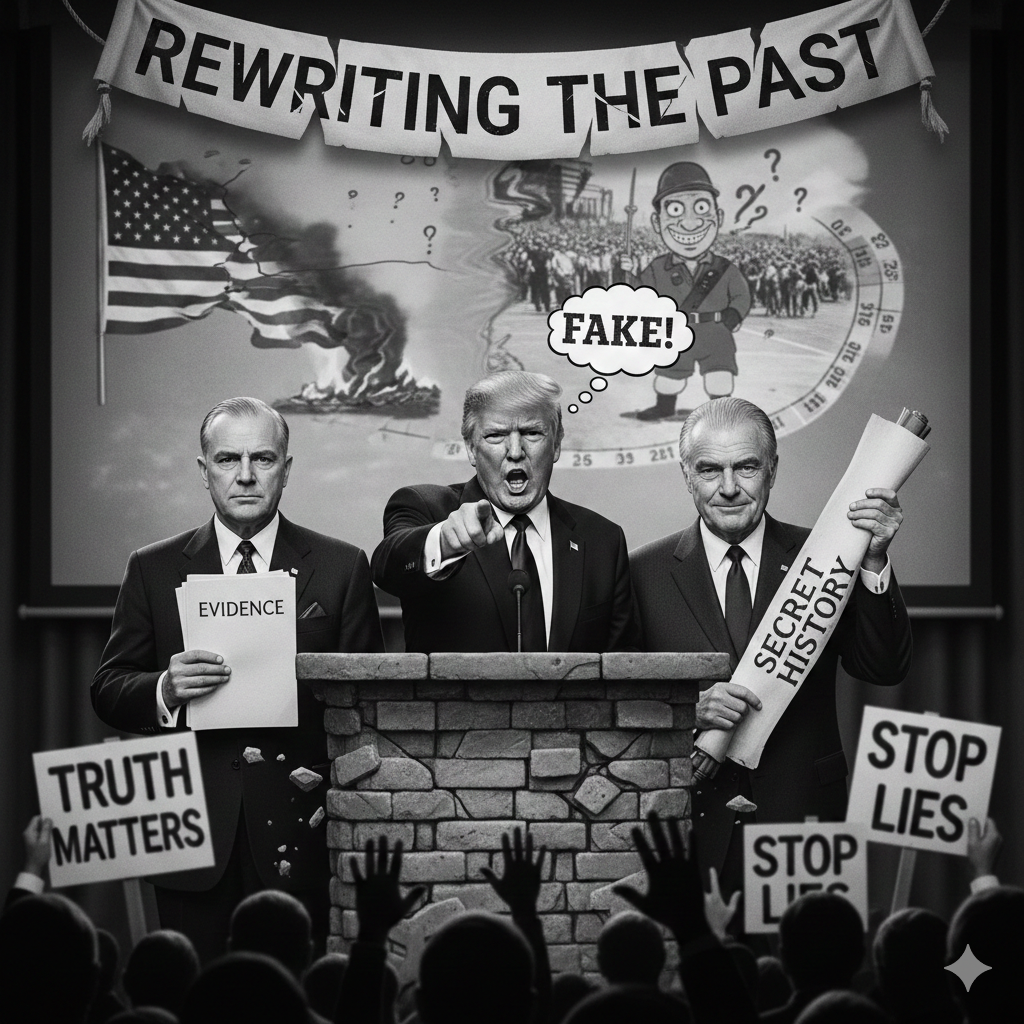

The events surrounding President Donald Trump and the January 6th, 2021, uprising at the U.S. Capitol are often cited by critics as a stark manifestation of these authoritarian impulses on the right. The movement, fueled by the “Big Lie” of election fraud, exhibited several features consistent with Adorno’s analysis: the authoritarian submission to a single, idealized leader (Trump) whose claims were accepted uncritically; authoritarian aggression directed at out-groups (Democrats, election workers, and institutional authorities) accused of violating conventional norms; and a belief that the “wide-awake citizen” should take the law into his own hands to overturn democratic outcomes. The violent attempt to halt the peaceful transfer of power—a foundational requirement of democracy—is, in this analysis, the ultimate expression of a political faction willing to discard democratic processes in favor of direct, unilateral assertion of power to preserve the perceived in-group order.

In conclusion, the strategy of associating democratic socialism with totalitarian communism was a potent political weapon that effectively leveraged Cold War anxieties long after the Soviet threat dissolved. However, this rhetorical move obscures the crucial constitutional difference: democratic socialism seeks change through accepted democratic channels, whereas communism demands the destruction of those channels. Furthermore, the psychological lens of authoritarian personality theory suggests that a vulnerability to strong, anti-democratic leadership exists across the political spectrum, providing a framework for understanding the willingness of some elements on the political right to engage in events like the January 6th attack, which fundamentally challenged the American democratic order.