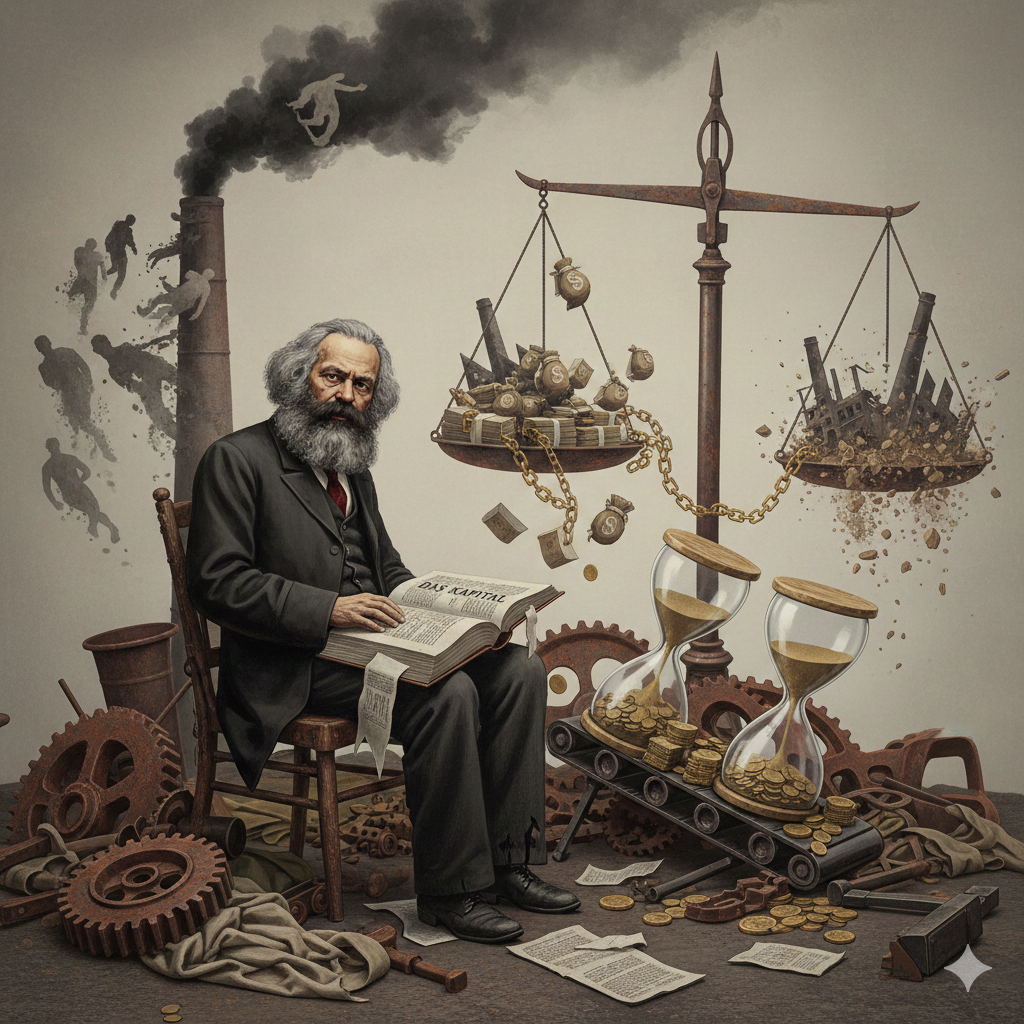

The Economic Inadequacy of the Labor Theory of Value

The Labor Theory of Value, as articulated by Karl Marx, posits that the economic value of a good is objectively determined by the socially necessary labor time required for its production.1 While this theory provided a potent rhetorical tool for 19th-century industrial critiques, it fails to describe how value actually functions in a modern economy. The fundamental error lies in the assumption that value is an inherent property derived from production inputs rather than a subjective assessment made by consumers.2 This is most evident in the “transformation problem,” where Marx struggled to mathematically reconcile labor values with actual market prices.3 If labor were the sole source of value, capital-intensive industries would logically be less profitable than labor-intensive ones, yet in reality, profit rates tend to equalize across sectors regardless of their labor composition.

Furthermore, the Marginal Revolution in economics demonstrated that value is subjective and determined at the margin—meaning the value of a good is decided by the utility of the last unit consumed, not the historical effort used to create it.4 A mud pie takes as much labor to make as an apple pie, yet it has no value because there is no demand for it. Conversely, items with little labor input, such as land or rare collectibles, can command immense prices due to scarcity and high demand. By tethering value strictly to labor, Marxist theory cannot account for the signals of supply and demand that actually coordinate resources in a complex economy.5 This rigidity makes the theory obsolete for calculating prices or efficient resource allocation, rendering it a poor foundation for economic planning.

Socialism as a Distributional and Ethical Project

The invalidation of the Labor Theory of Value does not, however, invalidate the political or ethical goals of socialism or social democracy. One does not need to believe that labor is the metaphysical “substance” of value to believe that the current distribution of wealth is unjust or that workers deserve a greater share of the economic output. Modern social democracy and democratic socialism have largely pivoted away from arguments about the origin of value to arguments about the distribution of surplus. The critique of capitalism can stand robustly on the observation that unregulated markets lead to extreme inequality, monopoly power, and the erosion of public goods, regardless of whether prices are determined by labor time or marginal utility.

In this framework, the focus shifts from the extraction of surplus value at the point of production to the democratic management of the economy and the welfare state. The moral case for socialism relies on the principles of equality, human dignity, and democratic control over capital, not on an accounting identity regarding labor hours. By accepting market mechanisms for price discovery—acknowledging that supply and demand are necessary for efficiency—social democrats can argue for high taxation, strong unions, and universal social programs. This approach treats the market as a useful servant rather than a master, ensuring that the wealth generated by market efficiency is distributed according to social needs rather than allowing market outcomes to dictate social stratification.

The Keynesian Resolution to Class Conflict

The inevitability of class conflict, a central tenet of orthodox Marxism, is effectively countered by the practical application of Keynesian economics.6 Marx predicted that capitalism would collapse due to internal contradictions, specifically underconsumption, where workers would be unable to afford the goods they produced, leading to spiraling crises. John Maynard Keynes acknowledged this potential flaw but demonstrated that it was not fatal if the state intervened to manage aggregate demand. By using fiscal policy, monetary tools, and government spending, the state can smooth out business cycles and maintain full employment. This fundamentally alters the dynamic between labor and capital, turning what Marx saw as a zero-sum war into a manageable partnership where both wages and profits can rise simultaneously.

Keynesianism provides the economic architecture for the modern welfare state, which acts as a mechanism for class compromise rather than class war. Through progressive taxation and social safety nets, the state redistributes the surplus necessary to keep consumption high, satisfying the economic needs of the working class while preserving the stability required for private investment. This synthesis effectively defuses the revolutionary potential of the proletariat by integrating them into the consumption cycle of capitalism. It solves the problem of “poverty amidst plenty” not by abolishing private property, but by ensuring that the purchasing power of the masses is sufficient to sustain the economy, thereby stabilizing society through policy rather than revolution.

International Law and the Mitigation of National Conflict

Just as Keynesianism addresses internal class conflict, the development of international rule of law and institutions like the United Nations offers a liberal solution to the problem of national conflict and imperialism. Marxist theory traditionally views international relations as an extension of class struggle, where capitalist nations are driven to inevitable war by the need to export capital and seize new markets. This perspective treats war as a structural necessity of capitalism. However, the post-WWII international order suggests that nations can resolve disputes through institutional cooperation, treaties, and collective security arrangements, independent of their economic systems.

The United Nations and the framework of international law provide a forum for diplomatic resolution that transcends the economic determinism of Marxist theory. By establishing universal norms, human rights standards, and legal channels for arbitration, these institutions create a buffer against the raw exercise of power. While not perfect, this system demonstrates that national conflicts are often driven by geopolitical security dilemmas or local grievances that can be managed through political and legal mediation rather than global revolution. The existence of a rules-based international order implies that peace is achievable through the deliberate construction of global governance structures, refuting the fatalistic notion that capitalist nations are destined for perpetual war until the global overthrow of the bourgeoisie.